Eurozone Debt Crisis - Italy and the Euro Unplugged

Interest-Rates / Italy Oct 04, 2018 - 02:22 PM GMTBy: Axel_Merk

Why is it that Italy causes such a stir in financial markets when proposing a budget? Is it politics or is the stability of the financial system at stake? In our assessment, the best way to avert a crisis is to allow market forces to play out. Let me explain.

Why is it that Italy causes such a stir in financial markets when proposing a budget? Is it politics or is the stability of the financial system at stake? In our assessment, the best way to avert a crisis is to allow market forces to play out. Let me explain.

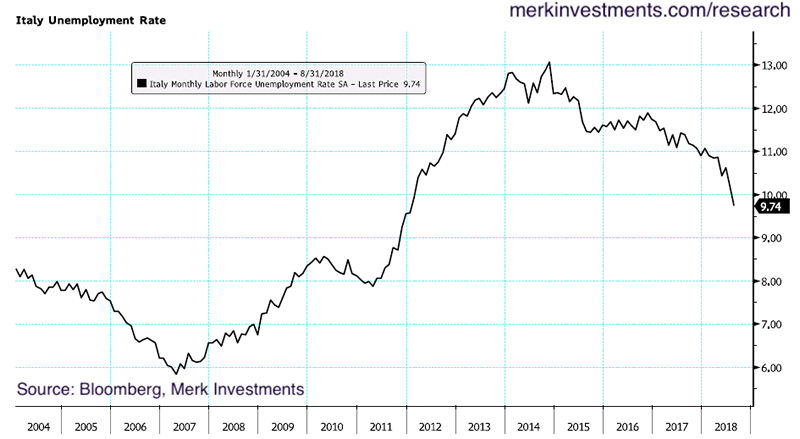

We all “know” Italy is in trouble. Well, before we jump to conclusions, let’s look at a few charts. Above is the Italian unemployment rate; it’s come off a high level, but still elevated. When policy makers call for structural reform, it is a codeword for increasing flexibility in the labor market, i.e. making firing easier. If firing workers is difficult, companies won’t hire workers. It’s also in this context that providing a so-called basic income is criticized by some as providing a disincentive to join the labor force (aside from cementing higher deficits for years to come). Basic income means you get paid, whether you work or not. In practice, the devil is in the details, as European workers have long enjoyed unemployment benefits; streamlining such benefits might actually save the government money. That said, Germany’s low unemployment, to a significant extent, may be due to the fact that welfare benefits were curtailed in 2002 (with a social democrat as chancellor), providing an incentive for workers to join the workforce.

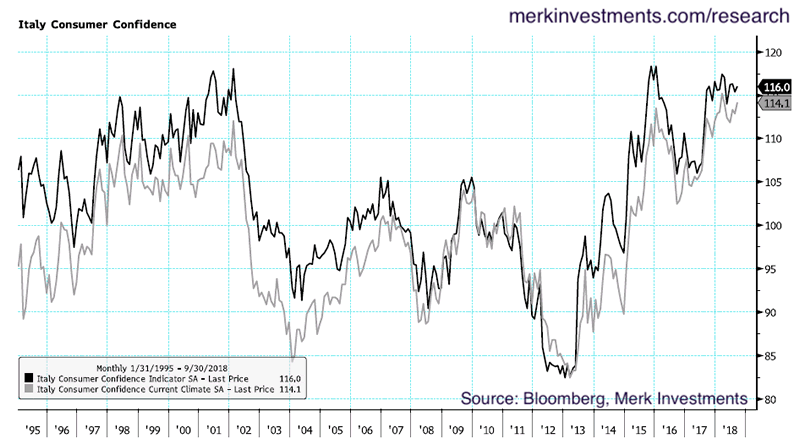

Moving on, consumer confidence in Italy is actually doing just fine:

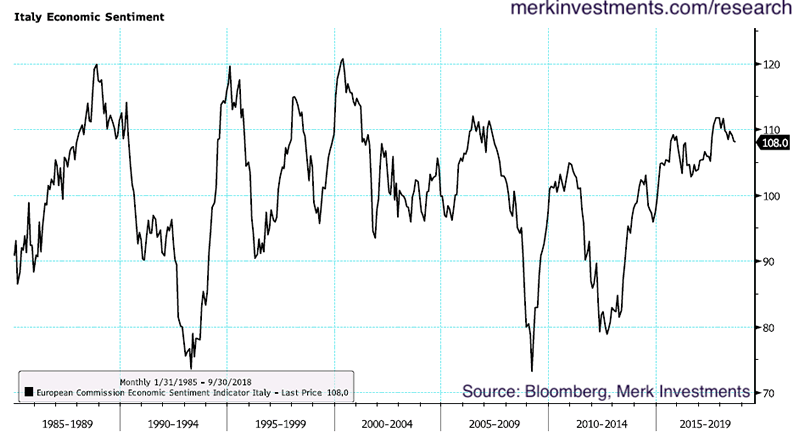

However, economic sentiment shows not everything is great – a problem as it suggests investments may be held back:

The big elephant in the room is Italy’s deficit. Italy’s total debt is larger than Germany’s, although the German economy is almost twice as large as Italy’s. As a percentage of Gross Domestic Product, Italy’s debt at 131.8% is rather high. Still, as can be seen from the chart below, Italy’s annual budget deficit has been shrinking for several years, most recently at 2.3%

Looking at the above chart, I can’t help but muse that weak or technocratic governments can’t get much spending done, but strong governments can. Italy currently has a populist government that intends to provide an economic stimulus. Keep in mind Italy is in its 66th government since 1946 (also note EU elections are coming up next year, with the coalition partners in Italy competing against one another on the EU stage).

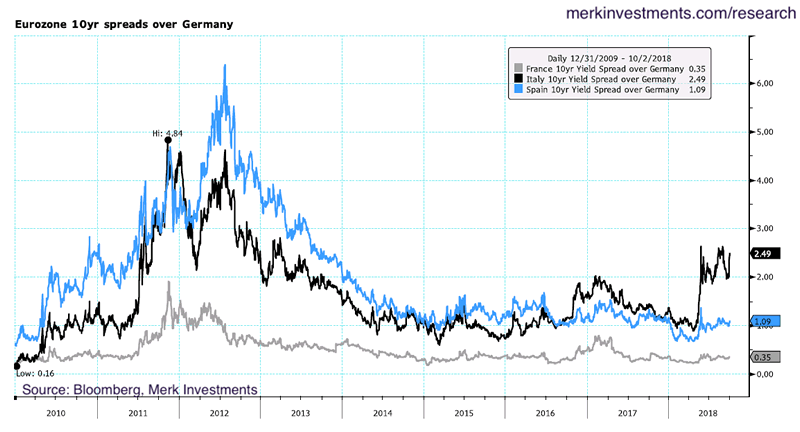

The chart below depicts the spreads of French, Italian and Spanish 10-year bonds over that of Germany. Germany has the lowest bond yield in the Eurozone; as such, the spread is the difference in yield, reflecting the higher borrowing costs of these countries for 10-year debt:

As can be seen, Italian debt had rallied up to a few days ago when the market expectations of a deficit below 2% for next year dwindled as concessions to the coalition partners lead to an announcement that next year’s deficit will be 2.4% (note: this is still a draft budget; and it’s also a target deficit, the actual deficit may well be different).

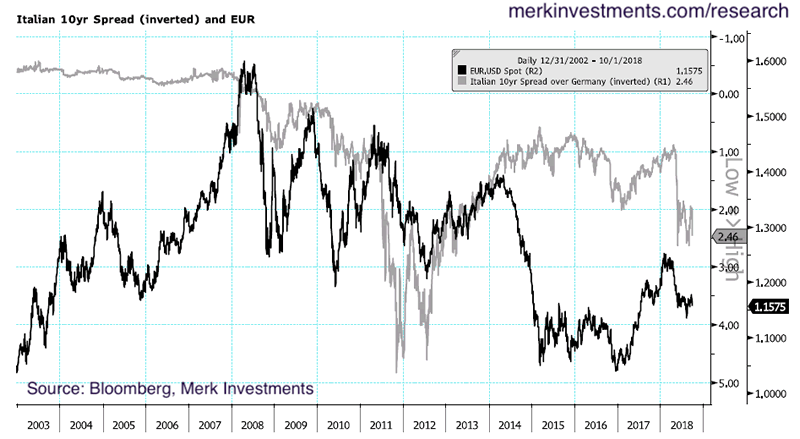

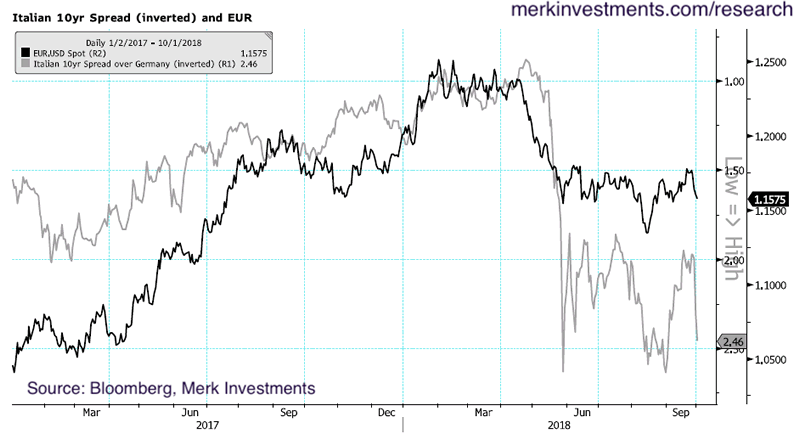

The reason why folks outside of Italy care about any of this is because Italy’s finances matter to the rest of the Eurozone. Notably consider the long-term and short-term charts of the euro versus Italian bond yields (y-axis for yields is inverted):

To be more specific, Italy has started to matter since the financial crisis.

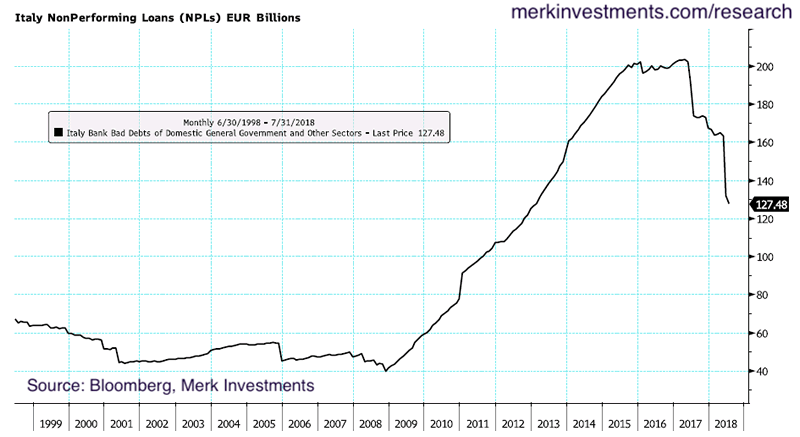

All that said, Italy has made progress in some areas that are worth mentioning, notably non-performing loans:

As a point of reference, the U.S. federal government estimates its budget deficit to be 4.2% of GDP in fiscal 2018. The possibly most significant difference between the U.S. and Italy is that the U.S. has its own currency. As such, the risk of U.S. government defaulting on its debt is minimal as it could always print its own currency; this creates a risk that the dollar’s purchasing power may erode, but minimizes default risk. In contrast, Italy is part of the euro and, as a result, has waived its right to print its own money.

In relinquishing authority to print money, Eurozone countries like Italy can be thought of more like states in the U.S., such as California. The key difference, however, is, that the U.S. government has broad fiscal powers, whereas there is not even an EU Treasury Secretary. The 2018 EU budget is €160 billion, a rounding error compared to the U.S. federal budget of over US$ 4 trillion.

All of this is by design as countries, such as Germany, don’t want to cede fiscal control to Brussels, afraid deficits would balloon. Ironically, a lot of the populist movement sweeping developed countries is about taking control back to the national level. As such, Italy should conceptually embrace that the EU doesn’t have its own Treasury. What Italy has a problem with is that Brussels is reviewing Italy’s budget in an attempt to tell it what to do. That’s because the Eurozone has agreements on deficits, notably to keep annual deficits below 3%; and, for highly indebted countries, to actively pursue measures to reduce their debt to GDP levels. And while 2.4% deficits may not sound like much, when the economy grows slowly, total debt-to-GDP will increase even with a deficit of “only” 2.4%.

This makes the Italian budget a political battle: firebrand politicians versus bureaucrats.

Some Italian politicians have also indicated deficits wouldn’t matter if the European Central Bank (ECB) explicitly guaranteed Italian debt, purchased it in unlimited amounts.

In my humble opinion, policy makers should be realistic and admit:

- Italian politicians cannot print their own money; and

- EU bureaucrats won’t be able to stop Italian politicians from pursuing their agenda.

I mention in my introduction that markets function best when market forces are allowed to play out. In the context of the above statement there’s a simple solution. Mr. Draghi should rescind his July 2012 statement that he would do “whatever it takes.” You cannot have your cake and eat it.

Long before the financial crisis, when Wim Duisenberg was still the head of the ECB (he’s the predecessor to Trichet, who in turn was Draghi’s predecessor), I argued that the way to make the Euro sustainable in the long-term would be for it to embrace, rather than fight, differences in fiscal discipline in the Eurozone. Let the policy makers do what they want to do and be held accountable, but not by Brussels bureaucrats: let policy makers be held accountable by the markets.

If we look back at the financial crisis, arguably the most powerful incentive for reform has been the market. Since the financial crisis, several rescue programs have been created, although it had also become clear that governments prefer to pursue extreme measures before asking for help when the cost of the help is to give up sovereign fiscal control. In this model, countries pursue their own fiscal policy; if they need help, they give up sovereign control. In that context, let me mention that I don’t endorse some of the chaos in the markets at the peak of the financial crisis. But be aware that crises will always happen; they are, however, less stressful when sound institutional processes are in place.

I have long argued that much of the work of European regulators should be focused on making the system more robust to failure. In the U.S., we have bank failures all the time, yet there’s no crisis because there is a robust process in place (the FDIC steps in). Similarly, especially in recent years, many steps have been undertaken to make the Eurozone more robust. In my assessment, that work needs to continue with the goal for the Eurozone to be able to stomach a sovereign default within the Eurozone.

There are those who argue Italy is too big to fail. That shouldn’t stop anyone from pursuing sound regulatory and monetary policy. Incidentally, just as regulatory policy is working to make the system more robust, monetary policy is moving towards holding countries more accountable. Consider:

- The ECB is expected to phase out its quantitative easing (“QE”).

- A first interest rate hike in quite some time may well come before Draghi retires.

- When Draghi retires, my best guess is a less dogmatic ECB chief will take charge. Consider that a lawyer became head of the Fed. The pendulum is swinging away from activist central bank chiefs.

- Inflationary pressures are gradually increasing in the Eurozone. Note the ECB’s inflation target is on headline inflation, not core inflation (Duisenberg and Trichet respected that; Draghi has all but ignored this despite his claim he pursues his QE policies to achieve the ECB’s legislated mandate). Draghi has indicated US fiscal stimulus may cause an inflationary spillover to the Eurozone; and that EU fiscal policy is also expansionary (more so if Italy implements its proposed budget!).

I mention the above because, in my assessment, they point to higher rates in the eurozone, as well as higher spreads. Higher spreads because, in our analysis, the main achievement of quantitative easing throughout the world has been a reduction of risk premia, i.e. a tightening of spreads, making risky assets appear less risky. As QE goes into reverse, risk premia ought to rise, causing spreads to increase.

In plain English, Italy should get used to paying more for its debt. Policy makers and market participants alike should stop the illusion that Italy will some day pursue German fiscal policy. It will not be the end of the world, nor the end of the Eurozone because risk friendly capital will gladly hold Italian debt – at the right price. The problem with a risk-free illusion is that you coerce risk-averse capital to hold risky securities. That’s a problem because the moment a reality check kicks in, risk-averse capital jumps ship. Aligning expectations with reality fosters healthy markets; artificial barriers create fragile markets bound to break under pressure.

As I indicated, we are moving in this direction as risk premia are bound to rise and regulators will continue to work to strengthen financial institutions. In this context, I argue the flareups we see in the markets will, with hindsight, be considered noise. I’m not suggesting there won’t be turmoil, but those who seek the relative safety of German bunds will pursue those; others interested in the higher yield may purchase Italian debt. What is unhealthy is to chase yield and live under the illusion that the additional yield is risk free.

The argument against this tough-love argument is that it could break countries, give rise to extreme parties. I would counter that in arguing that QE has been a key reason why populist governments have gained influence as one of its many unintended consequences. Printing money does not solve problems, only shifts the burden. At the peak of the financial crisis, I argued the best short-term policy may be a good long-term policy. I stand by that: stability is a result of a predictable, sound institutional framework. When the rules are clear, it ultimately benefits all stakeholders. And when mistakes have been made, someone has to pay for it. That includes governments that have spent too much money. The Eurozone isn’t structured to offload one’s debt problems to a central bank magic wand.

Please sign up for our free Merk Insights, explore our chartbooks and follow me on LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook or Patreon.

Axel Merk

Manager of the Merk Hard, Asian and Absolute Return Currency Funds, www.merkfunds.com

Rick Reece is a Financial Analyst at Merk Investments and a member of the portfolio management

Axel Merk, President & CIO of Merk Investments, LLC, is an expert on hard money, macro trends and international investing. He is considered an authority on currencies. Axel Merk wrote the book on Sustainable Wealth; order your copy today.

The Merk Absolute Return Currency Fund seeks to generate positive absolute returns by investing in currencies. The Fund is a pure-play on currencies, aiming to profit regardless of the direction of the U.S. dollar or traditional asset classes.

The Merk Asian Currency Fund seeks to profit from a rise in Asian currencies versus the U.S. dollar. The Fund typically invests in a basket of Asian currencies that may include, but are not limited to, the currencies of China, Hong Kong, Japan, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Thailand.

The Merk Hard Currency Fund seeks to profit from a rise in hard currencies versus the U.S. dollar. Hard currencies are currencies backed by sound monetary policy; sound monetary policy focuses on price stability.

The Funds may be appropriate for you if you are pursuing a long-term goal with a currency component to your portfolio; are willing to tolerate the risks associated with investments in foreign currencies; or are looking for a way to potentially mitigate downside risk in or profit from a secular bear market. For more information on the Funds and to download a prospectus, please visit www.merkfunds.com.

Investors should consider the investment objectives, risks and charges and expenses of the Merk Funds carefully before investing. This and other information is in the prospectus, a copy of which may be obtained by visiting the Funds' website at www.merkfunds.com or calling 866-MERK FUND. Please read the prospectus carefully before you invest.

The Funds primarily invest in foreign currencies and as such, changes in currency exchange rates will affect the value of what the Funds own and the price of the Funds' shares. Investing in foreign instruments bears a greater risk than investing in domestic instruments for reasons such as volatility of currency exchange rates and, in some cases, limited geographic focus, political and economic instability, and relatively illiquid markets. The Funds are subject to interest rate risk which is the risk that debt securities in the Funds' portfolio will decline in value because of increases in market interest rates. The Funds may also invest in derivative securities which can be volatile and involve various types and degrees of risk. As a non-diversified fund, the Merk Hard Currency Fund will be subject to more investment risk and potential for volatility than a diversified fund because its portfolio may, at times, focus on a limited number of issuers. For a more complete discussion of these and other Fund risks please refer to the Funds' prospectuses.

This report was prepared by Merk Investments LLC, and reflects the current opinion of the authors. It is based upon sources and data believed to be accurate and reliable. Opinions and forward-looking statements expressed are subject to change without notice. This information does not constitute investment advice. Foreside Fund Services, LLC, distributor.

Axel Merk Archive |

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.