Affording the Unemployed

Economics / Economic Theory Aug 18, 2010 - 08:56 AM GMT While the unemployment rate continues to hover between 9 and 10 percent, the average amount of time wage earners remain unemployed has skyrocketed to previously unrecorded levels.[1] Keynesians fear that a weak fiscal and monetary response will allow the presently cyclically unemployed to become so permanently.[2] UC Berkeley professor Bradford DeLong puts it briefly, "Long-term unemployment has a way of turning into structural unemployment."[3]

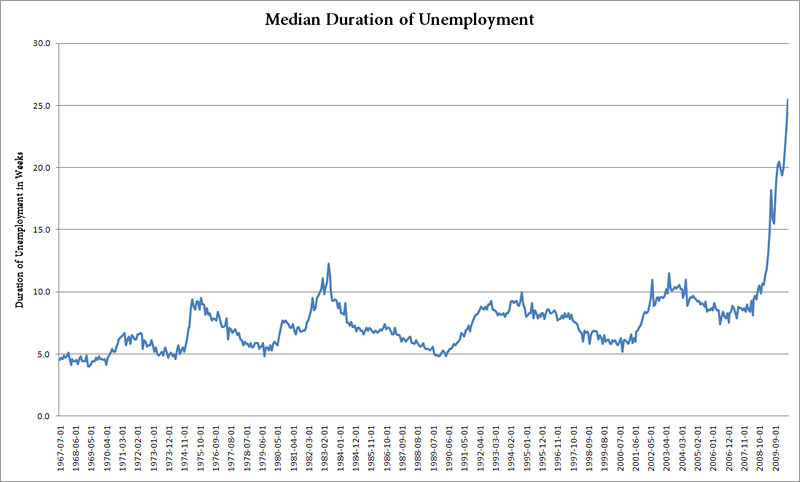

While the unemployment rate continues to hover between 9 and 10 percent, the average amount of time wage earners remain unemployed has skyrocketed to previously unrecorded levels.[1] Keynesians fear that a weak fiscal and monetary response will allow the presently cyclically unemployed to become so permanently.[2] UC Berkeley professor Bradford DeLong puts it briefly, "Long-term unemployment has a way of turning into structural unemployment."[3]

Paul Krugman, distraught over this alleged inaction on the part of the government and the Federal Reserve, explains the problem as one where those who remain unemployed for a long period of time will basically become unemployable.[4]

Paul Krugman, distraught over this alleged inaction on the part of the government and the Federal Reserve, explains the problem as one where those who remain unemployed for a long period of time will basically become unemployable.[4]

John Hopkins University professor Laurence Ball puts it bluntly, "These workers are unattractive to employers, or they don't try hard to find jobs."[5] The perceived problem is that the longer a worker remains unemployed, the likelier it is for said worker to lose relevant and marketable skills, or the less likely it is for that worker's skills to remain in demand.[6] As Ball writes, "Presumably it is more likely that the long-term unemployed become detached from the labor market if they can live on the dole indefinitely."[7]

The Keynesian solution, as usual, is to stimulate aggregate demand. Specifically, it is held that the timeliest solution is expansive fiscal and monetary policy.[8] Some New Keynesians are a bit more selective on what they believe the government should invest in. University of Oregon professor Mark Thoma, for example, argues that public investment in infrastructure is highly underrated. He points out that without the necessary infrastructure there can hardly be any creation of "good jobs," and in times such as these, where there are idle resources lying about, government can fill the gap by putting these resources towards providing the necessary infrastructure for future businesses to boom.[9]

Others, such as Bradford DeLong, are not as discriminatory. He writes, "At this point, anything that boosts the government's deficit over the next two years passes the benefit-cost test — anything at all."[10] Similarly, many point toward the Second World War as the quintessential event that solved a similar structural unemployment problem that arose during the Great Depression.[11]

But is the Keynesian analysis of current unemployment in the United States sound? The reliance on the stimulation of aggregate demand is paradoxical to the problem they are attempting to fix. Long-term unemployment cannot be permanently eliminated through willy-nilly fiscal stimulus or arbitrary aggregate demand shocks such as war, because these do not address the root of the issue — a change in the labor skills demanded. Neither are unemployment benefits useful in eliminating long-term unemployment. In fact, there is ample evidence that suggests that they may only cause the unemployed to remain unemployed for longer.[12]

Currently, those cyclically unemployed are the product of malinvestment that occurred during the boom and of businesses whose profits, perhaps damaged by recessionary monetary deflation, were insufficient to make the business cost-effective. Even conceding that long-term cyclical unemployment can turn into structural unemployment, the only viable solution to eliminating said unemployment is a dynamic, wealth-producing economy. It is true that employers are discriminatory, but as an economy grows and demand for labor grows with it, competition for labor will cause new employers to hire and train those who may not necessarily carry the right skills off the bat.

Unemployment Economics 101

Macroeconomists recognize two broad categories of unemployment: natural and unnatural. Unnatural unemployment is usually referred to as cyclical unemployment as it is a product of cyclical fluctuations — for example, those unemployed as a result of the present recession are deemed to be cyclically unemployed.[13]

Those unemployed because of reasons other than cyclical fluctuations are considered to be naturally unemployed. This category is further divided into frictional and structural unemployment. Frictional unemployment refers to individuals who voluntarily leave one job for another and reflects the amount of time between quitting one job and finding another.[14]

Structural unemployment, on the other hand, is involuntary only in the sense that it represents those forcefully laid off due to structural changes in the economy — this notion of involuntary is qualified below. It is usually assumed that those structurally unemployed do not have transferrable skills.[15]

Figure 2

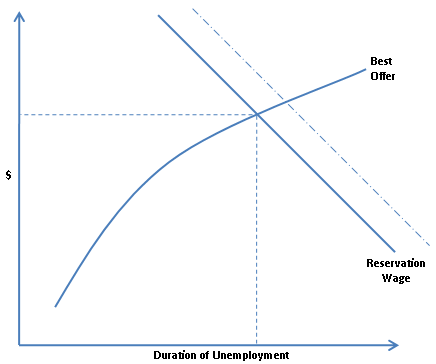

When modeling the individual unemployed wage earner, there is a general relationship between the individual's lowest acceptable wage rate (reservation wage), the best offer on the market, and the duration of unemployment. When freshly entering unemployment, a wage earner may have a high reservation wage, while there may not be any employer willing to offer that wage. As the duration of unemployment lengthens, the wage earner is likely to reduce his reservation wage, since finding a job becomes more imperative.

Furthermore, the longer the duration of unemployment, the better the offer the wage earner is likely to find. Theoretically, the exact duration of unemployment for any given individual is the amount of time necessary for the best offer and the reservation wage to meet.[16]

Free-market economists adamantly disagree with the notion that mass unemployment is possible in a completely free labor market. Ludwig von Mises went as far as to claim that in a free market such thing as involuntary unemployment is impossible, since if one offers his labor for low enough a price he will always find a buyer.[17] Of course, knowing that the market is in constant disequilibrium, one recognizes that involuntary unemployment is not necessarily impossible but simply rare and based only on imperfect information.[18] In short, outside of the existence of imperfect information, in a free-market the only limitation to employment is an individual's reservation wage.

Generally speaking, involuntary unemployment must be a product of government interventionism.[19] At its basis, involuntary unemployment is a product of disequilibrium between demand for labor and supply of labor, where the aggregate price of labor is too high relative to the aggregate demand for labor.[20] It stands to reason that such disequilibrium is likely to happen in the event of a cyclic fluctuation and from there we can logically deduct that the most efficient remedy to high unemployment is a fall in wages.

As mentioned above, the Keynesian framework tends to regard long-term structural unemployment as involuntary. The reason why an individual, who has been unemployed for what we assume to be a very long time, cannot find a job is because his skills are no longer applicable to the trade he is looking in. Such unemployment is actually voluntary in nature, because while the individual may not be able to find a job with similar pay to his last, there are nevertheless employers looking for labor in industries that require less skill, even if these employers therefore offer a lesser wage. Or an employer may offer the individual a lesser wage, but in exchange offer him the relevant training necessary to acquire the demanded skills. The individual rejects this offer because it is under his reservation wage. As such, this type of unemployment is firmly voluntary.

Now that we've reviewed the definitions of the various forms of unemployment, as well as why an individual may choose to be unemployed, and the nature of — and differences between — involuntary and structural unemployment, we are almost ready to proceed to the meat and bones of this issue. Before looking at the market's solution for a possible rise in structural unemployment, however, we must address the New Keynesian support of government unemployment benefits. Could these benefits really help the United States avoid long-term structural unemployment?

Public Policy and Unemployment

Paul Krugman argues that unemployment benefits, while perhaps counterproductive during periods of healthy economic growth, help stimulate aggregate demand.[21] The reasoning is that by distributing money to the unemployed, the government is directly funding the consumption of goods, and therefore increasing aggregate demand, creating much-needed jobs. In a healthy economy an extension of unemployment benefits may put upwards pressure on the unemployment rate[22] but in a recessionary period these same benefits will have the opposite effect through the stimulation of demand for goods and services.

What is brought into question here is not the moral case against unemployment benefits — for all intents and purposes, the moral case for or against unemployment benefits is to be considered superfluous to this discussion — but the economic argument against the perceived benefit of extending unemployment benefits to stimulate aggregate demand.

A wage earner faced with falling wage income will not necessarily use this money as a method to survive unemployed for a longer period of time (or, in other words, to raise his reservation wage), but instead to pay for what he may consider basic necessities that he could only afford on his previous wage income.

There is no objective law that coerces the unemployed individual to spend his unemployment benefits outside of what he considers essentials necessary to survive (food, rent, et cetera). In other words, there is no guarantee that unemployment benefits will result in greater spending outside of what the individual would have spent regardless.

The unemployed wage earner may, in fact, prefer to save part of the benefits. Whether or not the unemployed wage earner will spend his new government allowance is a function of the individual's time preference, and, given the increased intertemporal uncertainty that results from cyclical fluctuations, it is conceivable that the individual may prefer to save his new income rather than to spend it on consumer or final-stage goods. As such, there is a chance that this scheme would fail to temporarily stimulate aggregate demand.

Even assuming that those receiving unemployed benefits choose to spend their newly received allowances, this represents capital consumption.[23] As will be argued below, long-term employment relies on investment or an increase in demand for capital goods further away from consumer goods (a lengthening of the structure of production). By directly financing consumer goods, the government is instead financing the bidding away of resources from the capital-goods sector and is funding the consumption of capital. Without the production necessary to support such consumption, this inevitably leads to a net loss in wealth.

Imagine, for example, the food and agricultural industries. Let us assume that an unemployed wage earner receiving unemployment benefits spends the majority of his check on food. For the sake of simplicity, let us further assume that all ready-to-consume food comes directly from agriculture. Unemployment benefits necessarily funnel money from the saver to the consumer (even deficit spending must be funded through the sale of government bonds, unless new money is created ex nihilo), and so such a redistribution of wealth represents a movement of capital from higher stages of production to the final stage — or capital consumption.

It can be therefore concluded that the direct financing of capital consumption represents only a temporary rise in aggregate demand; it serves of little use in stimulating aggregate demand over the long run. Another way of putting it is that unemployment benefits are unlikely to provide a long-term solution to rising unemployment. The government should instead abandon these redistribution schemes in favor of allowing capital accumulation to take place in an economy, and therefore foster wealth creation that will lead to a sustainable increase in aggregate demand.

World War II and Unemployment

The Second World War has, for a long time, been nearly unanimously considered the event that finally catapulted the United States' economy out of the Great Depression.[24] Economist Robert Higgs challenges the notion of wartime prosperity, stating that

the war itself did not get the economy out of the Depression. The economy produced neither a "carnival of consumption" nor an investment book, however successfully it overwhelmed the nation's enemies with bombs, shells, and bullets.[25]

George Reisman accuses the idea of being a product of "absurdities,"[26] arguing that war leads to a drop in the standard of living, whereas healthy economic growth aims for a consistently increasing standard of living thanks to an essentially limitless demand for wealth.[27] Mises rightfully considered capitalism and war to be absolute opposites.[28]

Nevertheless, the vast majority of economists believe that the Second World War provided the necessary "demand shock" for the United States to escape from the Great Depression.[29] Given this demand shock, it is now claimed that the Second World War also stimulated the economy sufficiently to solve the long-term structural unemployment problem of the Depression.[30] Unknowingly, Keynesians show the crudeness of their logic by appealing to World War II.

Above, we established that structural unemployment is characterized by people who are unemployed with nontransferrable skills. They are, in essence, undesirable and unemployable. The Keynesian logic is that the demand shock of the Second World War somehow made these wage earners desirable and employable.

This flies in the face of their belief that long-term cyclical unemployment can become permanently structural. It is difficult to see how an unemployed person with nonapplicable skills would learn the relevant skills by fighting Germans in the European Theater or Japanese in the Pacific. In other words, the period between late 1941 and mid 1945 represents four years in which those who were unemployed during the Great Depression and conscripted continued to erode their existing skills, without learning useful new ones.

Whether one believes that the Second World War directly ended the Depression or that prosperity was returned only during the postwar period, the conclusion regarding the Depression's long-term structural unemployment problem remains the same. The period between 1944 and 1946 represented a necessary industrial change from a wartime to a peacetime economy. Factories previously earmarked to produce armaments now needed retooling to produce civilian goods.

In addition, millions of demobilized servicemen were entering the unemployed labor force. The amount of persons unemployed in the private sector between 1943 and 1945 amounted to roughly 40% of the employable population.[31] Knowing that skills acquired in the wartime industry — whether as military personnel or working in one of the many war materiel-producing factories — were essentially nontransferrable, it is clear that this problem of "structural unemployment" was actually one of economic stagnation in the private sector.

Cyclical Unemployment as a Function of General Productivity

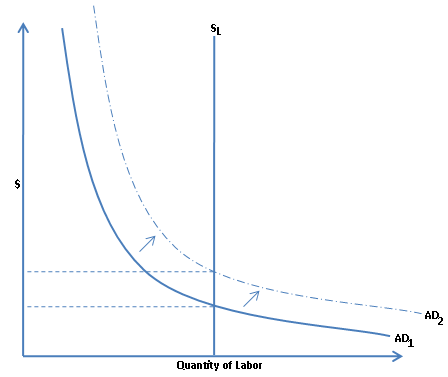

We know that any supply of labor can be accommodated to any demand for labor at a certain equilibrium price. Ultimately, all unemployment — except that produced by imperfect information or disequilibrium — is voluntary. Even the cyclically unemployed can be theoretically re-employed after a sufficient fall in wages. Only increases in productivity allow the labor force to remain fully employed at elevated wage rates. Figure 3 models this relationship, where the solid aggregate demand (downward sloping) line AD1 represents demand for labor at a certain point in time, and the dotted AD2 line represents demand for labor after an increase in productivity. Note industry is now able to employ the same amount of persons, SL (supply of labor), at a higher wage.

Figure 3

Business cycles generally cause an acute plunge in general productivity, due to the necessary liquidation of malinvestment. In periods of economic depression, an increase in productivity usually requires a previous rise in the employed labor force, itself requiring a fall in wages. However, this does not detract from the overall point that decreasing unemployment is not a function of increasing aggregate demand; rather, it requires an increase in sustainable productivity.

The relatively sudden increase in unemployment during depressions is attributable to the disequilibrium caused by credit expansion and the resultant malinvestment.[32] It is also fair to argue that given imperfect information the markets will not immediately adjust. As such, cyclical unemployment can exist in large numbers for a relatively short period of time. This period of time is usually marked by a decrease in the average wage level. Wages can only be restricted from falling by government-placed price floors, such as minimum wage. Therefore, long-term cyclical unemployment can only be attributed to government-enforced "sticky wages,"[33] or long-term unemployment benefits that make accepting a lower wage less urgent.[34]

This leaves us only with the supposed dilemma of a growing percentage of unemployed becoming undesirable due to skills attrition. The notion that some may become permanently unemployed due to a loss in skills is false on two major accounts:

-

The unemployed can accept employment in an industry that requires less skill, even if for a lesser wage. For example, Walmart is not likely to reject an ex-steel-mill worker simply on account of the worker losing his still mill-relevant knowledge.

-

As productivity increases, along with competition for labor, it is increasingly likely that employers will be willing to provide unskilled labor with the skills necessary to work within that industry, even if it is at the cost of a lesser money wage.

We therefore conclude that all long-term unemployment is the result of wage disequilibrium or insufficient productivity in the capital-goods sector. Long-term, involuntary structural unemployment is therefore virtually impossible.

Assuming an economy beset by general government intervention, wage-related price floors, and extended unemployment benefits, the only sensible method by which to approach full employment is fostering wealth creation. High long-term unemployment today has to do, not with unsolvable structural unemployment problems, but simply with government intervention in the form of price floors and benefits, which raise the reservation wage.

Discarding the possibility of a change in public labor policy, the only means of restoring equilibrium in the labor market is through a sustainable increase in aggregate demand for labor — an increase in private investment.

Notes

[1] Paul Krugman (July 26, 2010), "Permanently High Unemployment." Writes Krugman, "I really don't think people appreciate the huge dangers posed by a weak response to 9 1/2 percent unemployment, and the highest rate of long-term unemployment ever recorded."

[2] Ibid. Krugman comments on a paper by Laurence Ball, "Ball provides compelling evidence that weak policy responses to high unemployment tend to raise the level of structural unemployment, so that inflation tends to rise at much higher unemployment rates than before. And the kind of unemployment we're experiencing now, with many workers jobless for very long periods, is precisely the kind of unemployment likely to leave workers permanently unemployable."

[3] Bradford DeLong (October 31, 2009), "Long-Term Unemployment Turns into Structural Unemployment."

[4] Paul Krugman (August 1, 2010), "Defining Prosperity Down" (The New York Times). Krugman sums up the New Keynesian view by saying, "What lies down this path? Here's what I consider all too likely: Two years from now unemployment will still be extremely high, quite possibly higher than it is now. But instead of taking responsibility for fixing the situation, politicians and Fed officials alike will declare that high unemployment is structural, beyond their control. And as I said, over time these excuses may turn into a self-fulfilling prophecy, as the long-term unemployed lose their skills and their connections with the work force, and become unemployable."

[5] Laurence Ball (2008), "Hysteresis in Unemployment," Working Paper (John Hopkins University); p. 6.

[6] Bradford DeLong (August 1, 2010), "Yes, the Odds Are That Structural Unemployment in the U.S. Has Started to Rise." DeLong explains that these long-time unemployed workers are no longer desirable to employers. "That means that the chances are now very high that our cyclical unemployment is starting to turn into structural unemployment, as businesses that seek to hire and have the cash flow to hire still find that the currently-unemployed applying for jobs don't fit inside their comfort zones."

[7] Ball (2008), p. 24.

[8] Bradford DeLong (July 30, 2010), "Is America Facing an Increase in Structural Unemployment?." DeLong doesn't disappoint: "The solution is to rapidly boost aggregate demand: quantitative easing, raising the Federal Reserve's inflation target, banking policy to take more risky assets onto the government's balance sheet, and fiscal expansion."

[9] Mark Thoma (July 23, 2010), "America has underinvested in the public goods that support job growth." Thoma writes, "If we want the good jobs to locate here, we need the infrastructure to support them… Even with a recession as bad as this has been, a recession that makes investment in infrastructure cheaper than in normal times due to all the idle resources that are available, a recession that also makes the case for the jobs such investment spending provides, the case for public investment has been difficult to make."

[10] Bradford DeLong, "Deficit-Neutral Stimulus."

[11] Matthew Yglesias ("The Looming Structural Unemployment Disaster") writes, "The Depression Era teaches us that the manpower needs of a major global war would suffice, but otherwise who even knows."

[12] Such evidence is presented by Ball (2008).

[13] Roger A. Arnold (2008). Macroeconomics (Mason, Ohio: Thomson South-Western); p. 125. Arnold describes cyclical unemployment in relation to natural unemployment. "The unemployment rate that exists in the economy is not always the natural rate. The difference between the existing unemployment rate and the natural unemployment rate is the cyclical unemployment rage."

[14] Ibid., p. 124. "The unemployment owing to the natural "frictions" of the economy, which is caused by changing market conditions and is represented by qualified individuals with transferable skills who change jobs, is called frictional unemployment."

[15] Ibid., p. 215. Arnold puts it clearly, writing that "structural unemployment is unemployment due to structural changes in the economy that eliminate some jobs and create other jobs for which the unemployed are unqualified. Most economists argue that structural unemployment is largely the consequence of automation (laborsaving devices) and long-lasting shifts in demand. The major difference between the frictionally unemployed and the structurally unemployed is that the latter do not have transferable skills."

[16] Richard K. Vedder and Lowell E. Gallaway (1993). Out of Work: Unemployment and Government in Twentieth-Century America (New York: New York University Press); pp. 18–19.

[17] Ludwig von Mises (1998), Human Action: A Treatise on Economics (Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute); p. 595.

[18] Jesús Huerta de Soto (2008). The Austrian School: Market Order and Entrepreneurial Creativity (Cheltenham, United Kingdom: Edward Elgar); p. 99. Jesús Huerta de Soto corrects what he considers a neo-classical error of assuming equilibrium, "Nevertheless the real market is in a constant state of disequilibrium and, even in the absence of institutional restrictions (minimum wage laws, union intervention and so on), it is certainly quite possible that numerous workers who would be delighted to work with certain specific entrepreneurs (and vice versa) remain unemployed and never actually meet these entrepreneurs, or if the two do meet, they fail to seize the mutually beneficial opportunity to enter into an employment contract, simply due to a lack of sufficient entrepreneurial alertness."

[19] Mises (1998), p. 598. Mises established the relationship between government and what he calls institutional unemployment: "Catallactic unemployment must not be confused with institutional unemployment. Institutional unemployment is not the outcome of the decisions of the individual job-seekers. It is the effect of interference with the market phenomenon intent upon enforcing by coercion and compulsion wage rates higher than those the unhampered market would have determined."

[20] George Reisman (1990), Capitalism: A Complete and Integrated Understanding of the Nature and Value of Human Economic Life (Laguna Hills, California: TSJ Books); p. 580. Reisman clarifies, "…unemployment is caused by an improper relationship between money wage rates and the demand for labor in the economic system. Specifically, the average money wage rate is too high relative to the aggregate demand for labor."

[21] Paul Krugman (7 March 2010), "Supply, Demand, and Unemployment." Krugman argues, "And the truth is that unemployment benefits are a good, quick, administratively easy way to increase demand, which is what we really need. So right now they have the effect of reducing unemployment."

[22] Vedder and Gallaway (1993), p. 259. The economic argument against unemployment benefits revolves around the idea that these benefits will raise the reservation wage of the wage earner in question. As Vedder and Gallaway explain, "Three types of governmental policies raising the reservation wage in recent decades are worth mentioning: unemployment compensation, workers' compensation, and public-assistance payments."

[23] Mises (1998), p. 514. Ludwig von Mises explains capital consumption: "Capital consumption and the physical extinction of capital goods are two different things. All capital goods sooner or later enter the final products and cease to exist through use, consumption, wear and tear. What can be preserved by an appropriate arrangement of consumption is only the value of a capital fund, never the concrete capital goods."

[24] Robert Higgs (2006), Depression, War, and Cold War (Oakland, California: The Independent Institute); p. 1. Higgs writes, "Thus, one might consider separately the causes of the Great Contraction, the unparalleled macroeconomic collapse between 1929 and 1933; the Great Duration, the twelve successive years during which the economy operated substantially below its capacity to produce; and the Great Escape, generally understood to have been brought about, directly or indirectly, by American participation in World War II… Regarding the Great Escape, until recently, there seemed to be hardly any disagreement."

[25] Ibid., p. 98.

[26] Reisman (1990), p. 550. Reisman argues in favor of productionism and against the notion of beneficial war expenditure, writing that "in contrast to all absurdities, productionism recognizes that the need for wealth is always superabundant and thus that the last thing in the world that is necessary is to create more need for wealth by destroying existing wealth."

[27] Ibid, pp. 550–551. "It is also to cause people to work longer and harder, and people who otherwise would not have found it necessary to work, such as many housewives and teenagers, to go to work — all in an effort to offset the drop in standard of living that the diversion of output to the war effort causes. Similarly, the postwar replacement of wealth needlessly destroyed in war is at the expense of new and additional wealth that otherwise would have been enjoyed in addition to the wealth needlessly destroyed, and at the expense of leisure that people could otherwise have afford to choose."

[28] Mises (1998), p. 824. "Of course, in the long run war and the preservation of the market economy are incompatible."

[29] Paul Krugman, in his book The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008, argues, "The Great Depression in the United States was brought to an end by a massive deficit-financed public works program, known as World War II." As quoted in: Richard W. Fulmer (November 2009), "World War II Ended the Great Depression?" (The Freeman).

[30] DeLong (July 30, 2010). DeLong argues, "The last time the U.S. was in such a situation was at the end of the 1930s. Mobilization for total war cured the incipient structural unemployment problem with ease."

[31] Higgs (2008), p. 82. These include wage earners in military-oriented civilian production, civilian employees for the military, and military personnel.

[32] This is typical Austrian business-cycle theory which has been discussed elsewhere. See, for example, Mises (1998) and Reisman (1990).

[33] On sticky wages, see Robert Murphy's response to Gregory Mankiw: Robert Murphy (June 7, 2010), "Do Sticky Wages Weaken the Case for Markets?." Regarding sticky wages, Murphy writes, "As so often happens, the proponents of government intervention are pointing to a problem that is greatly exacerbated by the government itself."

[34] Ibid. Murphy argues, "In our times, the extension of unemployment benefits is the most obvious example of a government intervention that prolongs job searches. Rather than accepting a job for lower pay than they are accustomed to, laid-off workers can continue their quest for much longer than would be the case in a free market." Murphy points out that Chicago School economist Casey B. Mulligan and New Keynesian economist Gregory Mankiw agree.

Jonathan Finegold Catalán is an economics and political science major at San Diego State University. He blogs at economicthought.net. Send him mail. See Jonathan M. Finegold Catalan's article archives.![]()

© 2010 Copyright Ludwig von Mises - All Rights Reserved Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

© 2005-2022 http://www.MarketOracle.co.uk - The Market Oracle is a FREE Daily Financial Markets Analysis & Forecasting online publication.